I recently read a recommendation about a tool about Data Governance and how this tool would solve every data governance problem in an organization. Then, I went back in time, and I remembered how the CEO of a software company told me that a client that we had in common would have plenty of cash to buy costly software from his company by using the tool that he just sold them. I was very skeptical about his prediction, but I couldn’t precisely pinpoint the problem at that moment. So I gave it much thought, and I finally found the explanation I was looking for.

The False Premise

The tool was a business intelligence software that depicted the inventory status of all stores in the company. With this intelligence, the supply chain manager could replenish the available inventory and the inventory by store. However, each store had its own profile, the type of clients was very different from store to store. Furthermore, most of the products were imported; thus, replenishment to the main inventory was tricky. Everybody that works with supply chain management is aware that dead inventory is the main enemy of a company: it is money sitting there that any day can become a liability. Therefore, moving the inventory as fast as possible should be the rule, and detecting sitting-duck products in the stores and the warehouses is a priority.

However, this kind of work requires, first of all, people. Detecting the products is not the main problem: it is moving the products. This type of activity requires collaboration, communication, and leadership. For example, moving the inventory needed the list of products that needed moving and the knowledge of the clients that every store served. Of course, an intelligence tool makes this work easier and better, but the process and commitment to perform the activities come from the people involved. The process is born from the intrinsic knowledge of the people that perform the action. A manager or someone who knows the theory very much can devise an approach. Still, only the people involved in the everyday activity know those little details that make the difference between a wish and a goal. This company lacked synergy amongst its employees; the management worked top-down, and a policy always came from above without considering the feedback from the people who did the work.

The vendor explained the technicalities, the beautiful dashboards and described a good picture of how the inventory would move and generate the cash needed to solve all the company’s problems. A very nice summary and review about supply chain management complemented with pictures were presented, and the sale was made. But, unfortunately, ten years later, they still didn’t have enough cash to buy the expensive software.

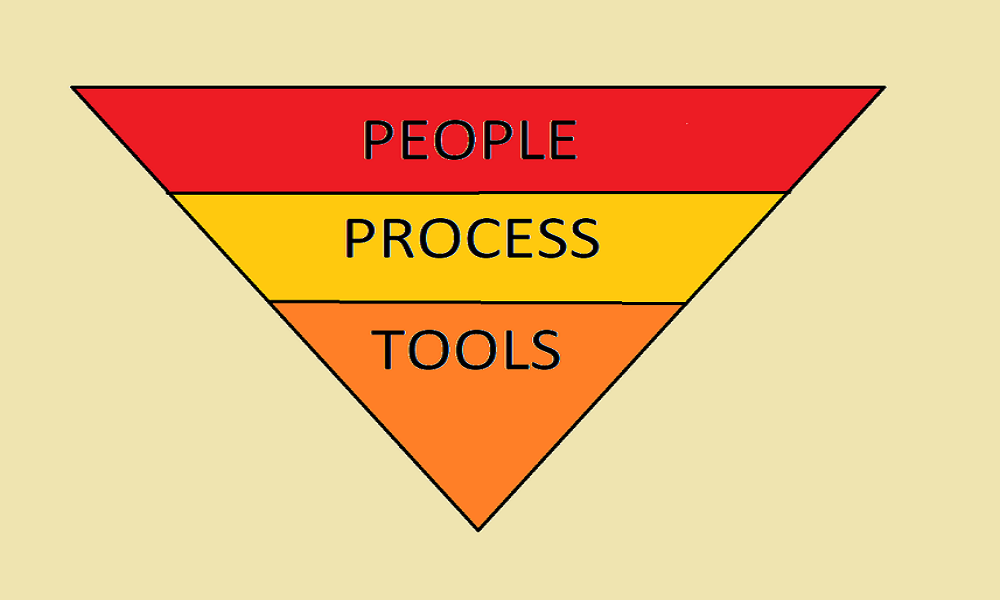

People over Process

When an organization needs to implement a process or solve a significant problem, the best way is to involve all the people in the process and devise a prototype solution. It may work or not, and in the best cases, it would be a good start that would generate information to improve the process as with any prototype. The starting point is solving a subset of the problem: the simplest is the best approach. However, the company should have a culture of change and a managerial staff ready to hear any suggestion, good or bad. Good advice may come from very unexpected places. Most people feel motivated just by being listened to and recognized; being part of something is, most of the time one of the best rewards. If there is no culture of listening, it is challenging to implement changes that impact an outcome.

Process over Tools

If the company has had this virtue, the next step would have been to create a process to replenish one store using the new procedures. Maybe a good start could have been to choose just a group of sitting-duck products. The company wouldn’t need to purchase a tool for that, and the inventory manager could have got the products that were not moving in the last six months, for example. The selection of the products is related to the cost, season, and store. Then, the sales department, the sales store manager, the supply chain manager, and the inventory manager could have devised a process.

Again, there was no need for a tool; the process could have been implemented using what the company had at that moment that included an IT department. Then the next step was to research and then getting the process in better shape using the results, or the worst-case scenario: to start again. But this time, they could have created the new method using the knowledge gathered during the experimentation stage. The updated process could have included more stores to further the analysis. This fact is critical because each store had a different type of client. Once the process was developed and yielding good outcomes, they could have started looking for tools.

Organizations may be of significant scale; thus, a prototype may not be able to be upgraded to full scale unless there is software in place. However, investing in a tool without a thorough understanding and a plausible solution is a waste of good money. Furthermore, it can cause disappointment amongst the employees who are asked to implement the tool, knowing that it will not work.

Some History

The concept “people over process, process over tools” was first introduced in Scrum and included in the values of DevOps. It is interesting to note that both frameworks were developed by practitioners who researched their organizations. They named the values using their own experiences and realized that the problems were the same among peers. Sure, they did thorough research, and they also made their prototypes, but they also implemented these new frameworks in their companies. Both frameworks are in constant review, and both frameworks started with people getting together to solve a big common problem in the IT field. People first. Nice!!!

I like to look for good historical examples to discover patterns and realize how people have changed so little over time. In my search, I found that The Battle of Thermopylae contains elements that depict what “people first” is trying to convey. In the year 480 BC, an army of about a quarter of a million from the Achaemenid Empire of Xerxes I, according to Herodotus, fought against 7,000 Greeks lead by Leonidas I, King of Sparta. The battle lasted three days; the Greeks successfully resisted the Xerxes’ army for the first two days.

They used the narrowest part of the path to confront the enemy and cause the most damage with scarce resources. The Greeks were highly outnumbered, but using their famous phalanx formation, they could have resisted the invasion for a long time; this battle was not a suicidal mission. However, the Greeks were betrayed by Ephialtes, who showed the Persians a small pathway to avoid the pass on the third day. The Persian forces flanked the Greeks, who fought to the last man to defend the position. When King Leonidas got the news about the trespassing, he sent the allied forces to retreat, but he and the Spartan forces stayed with 2,000 allied soldiers. The Persians finally got into Athens and destroyed the city. Still, there was enough time to gather and organize the troops, and the Greek coalition defeated the Xerxes’ army in the Battle of Salamis and the Battle of Plataea. In both battles, the Greek and allied forces used the battle cry “Thermopylae, Thermopylae!!!” It is said that the forces were infused with patriotism by the sacrifice of the 300 hundred and their King.

People over process and tools, as mentioned before, relate to leadership, collaboration, and empowerment: people working together towards finding a common goal or solve a complex problem. A clear example of leadership is King Leonidas’ actions. Leonidas sent an army of 7,000 soldiers to the Thermopylae, pass along with 300 Spartans against an army of a quarter of a million Persians. That is too much to ask if we see it from a distance as we are doing it right now. However, he went and fought along with their peers; that is leadership. He didn’t ask his fellow soldiers anything more that he would do to defend his country.

Collaboration comes with the combined knowledge of the allied forces and the Spartan soldiers. For example, the phalanx formation was a highly effective war tool to fight the enemy; however, it required a close collaboration amongst the soldiers to accomplish the impenetrable block formation. Herodotus described how the Spartans were bombarded with so many arrows that the sky was obscured by the attack’s shadow, and even then, the phalanx was ironclad; none of the Spartan soldiers were harmed.

Empowerment can be seen when Leonidas commanded the soldiers to leave after realizing that they were about to be flanked by the Persians using the secret road behind them. Nevertheless, the Spartan soldiers stayed, and 2,000 allied soldiers also chose to be there; It was better to die fighting for the freedom of their country instead of falling under the slavery of Xerxes I. It is essential to notice that the Immortals, a 10,000 elite division with an avalanche of resources in the form of arrows, elephants, war carriages, and so many more war tools, couldn’t defeat the Grecian coalition during the first two days.

They finally lost not because of the enormous resources invested by the Persians but because the Greeks were betrayed. We can fantasize that if this treason would not have happened, the small Grecian army could have held the position using the values instilled in the Spartan way of life and their enormous force of will first, and then by well-defined methods of war. Thus, we can see that people made this impossible tale of courage possible, and their sacrifice inspired the rest of the Grecian coalition to finally defeat Xerxes’ army.

Further Reading

Going fast forward, 2,500 years at least, right into this century, I recommend the book “The Unicorn Project” by G. Kim, who describes how an elite team got together to overthrow the overlord of bureaucracy to modernize an entire business and technological operation in a company with overwhelming challenges to stay on top of the competence. Maybe it is not a story as romantic and poetic as the 300 Spartans who died along with their king to defend their country. Still, it is a comprehensive tale of what can happen when people get together to solve a highly complex problem. I can attest to the integrity of the problems, failures, and dramas presented in the book: I lived a smaller version of them. For me, it was a vivid experience. It was so real that I had to stop reading chapter six to take Advil because the narrative reminded me of many dramas in my professional life that I relived. For example, I can remember updating an error in the production version of the software and paralyzing the whole company’s operation for a couple of hours. It was horrific to remember that, but, as any good horror story, I kept reading, and the book had a happy ending: Van Helsing killed Dracula in the end.

Finally, I know how to answer the happy CEO who sold his tool to his client, but next time, I would rather help the client put in place a comprehensive solution designed by their own people before buying any tool. But only if they are willing to listen to everybody’s suggestions no matter how good or bad the suggestions could be.

Resources

The Battle of Thermopylae is a summarization from Wikipedia, Battle of Thermopylae – Wikipedia

Interesting article about People in the Scrum world, When it comes to agility, people come before process | PA Consulting by Amy Finn